By Wayne Stapleton

By Wayne Stapleton

VP of Cross-Cultural Engagement and Emerging Leader Engagement

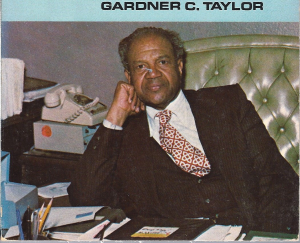

Each Black History Month provides the opportunity to look back and acknowledge the contributions that African Americans have made. As a conference of churches, we acknowledge the unique ways brothers and sisters in Christ of African descent have advanced the Kingdom of God. This Black History Month, we want to draw attention to pastor and leader Dr. Gardner C. Taylor. Dr. Taylor was once quoted as saying, “It is not in the tone of the voice; it is not in the eloquence of the preacher; it is not in the gracefulness of his gestures; it is not in the magnificence of his congregation; it is in a heart broken and put together again by the eternal God.” Dr. Taylor displayed such a heart. He sought to be, as he put it, a “transmitter of the gospel.” And he did so in word, through faithful preaching, and in deed, serving his community as a shepherding Christ-follower, being himself a sign and servant of the Kingdom of God.

Gardner Taylor pastored Concord Baptist Church of Christ in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, for forty-two years. His influence was local but also reached well beyond New York. A 2015 New York Times article commemorating his life and ministry states that “his impact as a speaker, writer and political force in the city and in a nation of long-segregated schools, churches and other institutions reached far beyond his 10,000-member congregation.”

He was a servant of God whose service in ministry stood large. As a preacher of the Gospel, he has been recognized for his faithful and passionate service. In 1980, Time magazine named him “the dean of the nation’s black preachers.” An article in The Christian Century referred to Taylor as the “poet laureate of American Protestantism.” In 1996, Baylor University noted him as one of the most effective preachers in the English-speaking world.As a shepherd in his local community, Dr. Taylor was deeply involved in that same community. In a 1995 article on Taylor’s life in Christianity Today, Ed Gilbreath wrote: “Taylor’s holistic grasp of the gospel has resulted in a church that serves as a model for urban congregations across the nation with its commitment to community outreach and development. With Taylor at the helm, Concord established a senior citizens’ home, a fully accredited Christian grade school, a professionally staffed nursing home, and an economic-development program that draws on a $1 million endowment to provide grants to various social projects in the Brooklyn area.” Taylor was missional.

Taylor was the grandson of emancipated slaves, his own father a pastor. He was born in Louisiana and educated in segregated schools. He wanted to be a civil rights lawyer, but in his era no Black person had ever been admitted to the Louisiana bar. His life dramatically turned directly and clearly toward Christ after he was involved in a car crash at 19 that left two white men dead. “The best I expected was probably years in prison,” he told The New York Post in 1958. “The worst could have been a lynching.” But two witnesses, both white men, testified that Taylor was not at fault. He later said of the incident, “In that day, for a white person to tell the truth about a black person in that situation was incredible; but those men told the truth. I would not be here today if they had not.” Instead of attending law school, Taylor went to Oberlin College in Ohio, earning a divinity degree in 1940.

He pastored briefly in Ohio and Louisiana before taking over the pastorate of Concord Baptist Church of Christ in 1948, which, with 8,000 members, was the second largest Baptist congregation in America at the time. Concord was founded in 1847 and was led by abolitionists in its early years. It was a sanctuary for runaway slaves, its second pastor actually being one himself. Later on, the church had a history of pastors known for helping the descendants of slaves and black migrants from the South. Dr. Taylor’s commitment to civil rights work upheld the church’s traditions.

Taylor recognized the role of the Black church in the lives of African Americans. He once noted, “One of the great contributions of the black church was giving to our people a sense of significance and importance at a time when society, by design, did almost everything it could to strip us of our humanity. But come Sunday morning, we could put our on dress clothes and become deacons, deaconesses and ushers, and hear the preacher say, ‘You are a child of God’ — at a time when white society, by statute, custom and conversation, just called us ‘n*****s.’ How could we have survived without a sense of God and the church telling us that we do matter? Where would we have been if there had been nowhere we could be told that we matter?”

Dr. Taylor was committed to racial justice. He organized civil rights marches and was arrested three times during protests in the 1960s. But it is said he was known more for his quiet activism than his militant protest. Dr. Taylor took on roles of responsibility and leadership, directing the Urban League of Greater New York and serving as a member of the New York City Commission on Intergroup Relations and as one of the leaders of the Kings County Democratic organization.

Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. named Dr. Taylor to the New York City Board of Education in 1958, the second Black member in its history. In the three years he served in this role, he attacked de facto segregation in city schools, arguing that federal aid should be denied private schools while public schools were desperate for funds.

Taylor’s wisdom comes through in his notable quotes. In a 2009 interview, Taylor said this on pastoring: “The first job of a pastor is to love people. That may sound syrupy, but it’s true. If a preacher [. . .] does not love people, forget it. On the negative side, they will test your love 25 ways to Sunday, but that’s the negative side. There are positive sides also. My God, you got to love them.”

Taylor was not alone in his struggle to love and serve others. For fifty-two years, he was married to Laura Scott Taylor, an accomplished intellectual and community leader in her own right; the founder of the Concord Baptist Elementary School, she served as principal for thirty-two years without ever being paid.

In response to the question, “What makes a great preacher?” Taylor answered, “In the Book of Ruth, Naomi says, ‘I went out full, and I’ve come back empty.’ That’s the story of life. It’s also the story of preaching; we must keep ourselves full so we can empty ourselves in the pulpit.”

Taylor’s life and ministry remind us of the goodness of our God, experienced by any and all who place their trust in him. At the end of his sermon “A Promise for Life’s Long Pull,” he offers a word on his life’s ministry, drawing from his favorite Black spiritual, “There Is a Balm in Gilead:” “‘Sometimes I feel discouraged and think my work’s in vain’ [. . .] But then, just at the end of my tether; but then, when all of my strength seems spent and gone; then, when I come almost to the borders of despair; then, when I feel frustrated and confused and out of it; then [. . .] the Holy Spirit comes and ‘revives my soul again.’”

The Holy Spirit revived Dr. Taylor’s soul as God indeed revives our own souls. And we are thankful for this.